When I walk alongside the river, I notice ducklings drifting by, decaying piles of invasive wintercreeper vines, amur honeysuckle peeking through scatterings of gravel pebbles, and families gathered for picnic lunches. With each step, I wonder about the footprints that have faded into the earth, but nonetheless touched this ground, and the ones that will leave a mark after me. I ponder my relation to our common home that Pope Francis describes in Laudato Si’.

As I bike back to my studio, the loud whoosh of cars speeding past makes me aware of our integral ecology, how the climate crisis disproportionately affects the most vulnerable neighbors in Christ. Breathing in the exhaust alerts me to the power lines, pipelines, aggressively embedded but only subtly demarcated, flowing in paths parallel to the water. Furthermore, invisible but influential red lines outline places with higher temperatures, less concrete, fewer trees. These lines of power separate the river from neighboring people whose water comes from the same source. As we know from the sacrament of baptism, water is a source of life. From collaborating with the Concerned Citizens of Charles City County to communicating the dangers of landfills, I have found that art can be a socially- and environmentally-engaged practice that creates space for dialogue. Through art, we can address the violence that harms our neighbors and our common home.

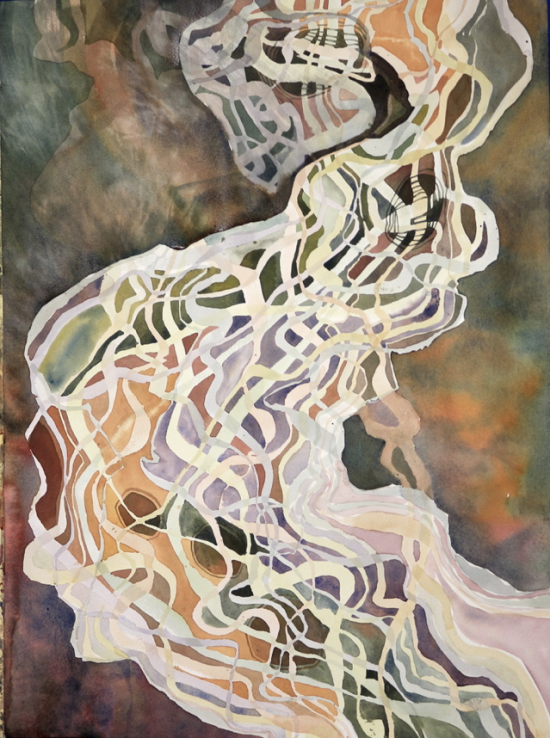

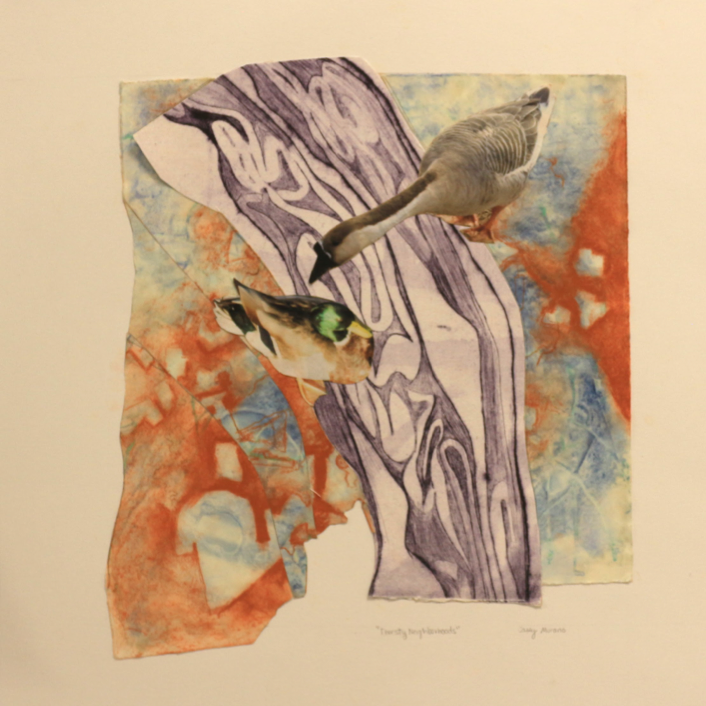

As in the Bible, stories of thirsting and drought are part of this watershed, but so is resilience. John Phillip Newell’s book Praying with the Earth, songs from Taizé, and weekly worship services are some of the contemplative approaches to prayer that sustain me in the collective work of building God’s kingdom on earth. Artmaking is a spiritual practice, a prayer practice that helps me cultivate sacred relationships and grounds me in our collective call to care for creation. Through the process of making layered oil paintings, collages, and watercolor monotypes based on plein airstudies at the river, I explore our vocation as pilgrims on this journey of life, called to walk gently, intentionally, in radical solidarity with one another.

“’Aha Makavis the true name of our people, given to us by our Creator who loosed the river from the earth and built it, into our living bodies.

Translated into English, ’Aha Makavmeans the river runs through the middle of our body, the same way it runs through the middle of our land.”

–Natalie Diaz, “The First Water is the Body” (2020) from Post-Colonial Love Poem

Casey Murano is a senior about to graduate from the University of Richmond with a major in art and minor in geography. In her art practice, she uses plein air painting and other practices to promote environmental justice through the lens of faith. She loves walking, observing ducklings on campus, sharing meals with friends, and spending time in the Office of the Chaplaincy. In August, she will be moving to St. Paul, Minnesota for a service year with the St. Joseph Worker program.